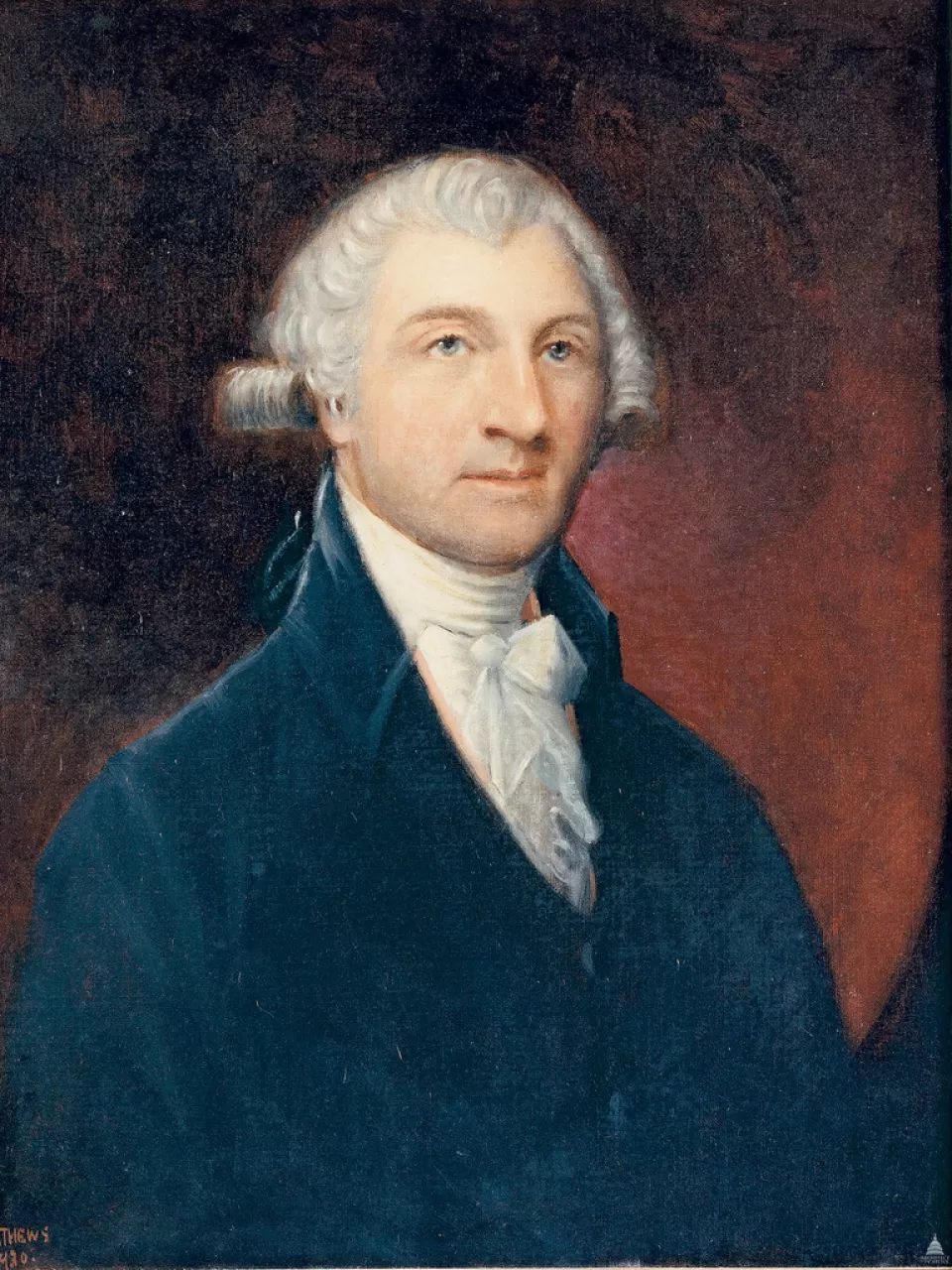

The first President of the United States, George Washington, passed away on December 14, 1799. While the country was mourning, one doctor refused to accept and devised a plan to resurrect George Washington. So let’s examine how one physician attempted to bring George Washington back from the dead.

The Day George Washington Died

On December 13, 1799, George Washington rode his horse through hail, snow, and cold rain. Washington didn’t even pause to change out of his wet clothing because he hated being late and was hurrying home for dinner. Washington may have arrived at the table on time, but his timeliness cost him dearly.

Later that evening, the former president awoke struggling to breathe while grasping his chest. Colonel Tobias Lear, the president’s top adviser, hurried to get a doctor as his wife, Martha, desperately screamed for assistance. Dr. James Craig, who had been caring for Washington for more than 40 years, and George Rollins, a specialist in bloodletting, were the two men who responded to the call.

Both entered the home and tended to the president’s health throughout the night. Washington received a tonic from Colonel Lear that was concocted with molasses, butter, and vinegar. That nefarious combo came close to choking the president. Rollins would draw blood every few hours to lower the president’s fever.

By the evening of December 14, Rollins had removed almost 40% of the blood from the president. Sadly it was for nothing. On December 14, 1799, soon after 10:00 PM, George Washington passed away due to a viral infection and bloodletting procedures.

Resurrecting A Plan

In an effort to save the president’s life, Dr. William Thornton hurried to Mount Vernon. Thornton was convinced he could end Washington’s suffering since he was an expert in tracheostomies, which were risky surgical procedures in the 18th century. Thornton eventually showed, but it was already too late. Washington had already passed. Twenty years later, Thornton described the scene. He claimed to have seen Washington “laid out, a stiffened corpse,” and that the loss of his best friend had left him speechless.

Dr. Thornton, however, wasn’t quite ready to give in to death just yet. Thorton was full of swagger and thought he could revive Washington. Thornton was knowledgeable about tracheostomies and the history of blood transfusions in the 17th century. The method was outlawed in France as a result of these procedures’ high level of risk, but Thornton remained optimistic about its potential.

Thorton, a graduate of the top medical schools in Europe, was well-known for his use of cutting-edge treatments in 1799. He was born in the West Indies in 1759, although he was raised in England. After migrating to the US and obtaining US citizenship, he continued his medical training in France and Scotland.

Dr. Thornton was also an amateur architect in addition to his medical expertise. In fact, he was chosen to design the US Capitol building, Thornton is best remembered as the country’s first architect. This distinction was given to Thornton in 1793 by George Washington himself. Thornton received a payment of $500, or around $15,000 in 2022. A construction plot in Washington, DC, as well as a friendship with the nation’s first president, were also bestowed upon him.

The Beginning Of Blood Transfusions

Now, before we go on, let’s jump back to 1492. 1492 was a big year for several reasons. That’s when Columbus arrived in the Americas, but there was also the very first known attempt at a blood transfusion.

It occurred when Pope Innocent VIII fell into a coma. His physician suggested blood and recruited three young boys to donate blood to the Pope. The technology to inject blood intravenously didn’t exist. So, according to one account, the physician poured blood into the pope’s mouth. To state the obvious…it didn’t work. The Pope died and so did all three boys.

Moving blood would once again be at the forefront due to William Harvey’s ground-breaking medical research in the 1620s. Harvey proved that blood circulated throughout the body, proving that a person’s veins could be filled with fresh blood. Scientists created metal instruments that could inject blood into veins around the 17th century. This fusion of science and technology sparked a surge of blood experiments.

The first people to test Harvey’s theory were researchers at the Royal Society in London. They experimented on animals rather than attempting a transfusion between humans.

Blood Between Humans & Animals

In 1656, Christopher Wren, best known for creating London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, put William Harvey’s idea to the test by injecting wine and ale into a dog’s veins. Unsurprisingly, the dog became intoxicated. Wren’s experiment demonstrated that the alcohol flowed throughout the dog’s body through the veins. Then, a doctor named Richard Lower, a colleague of Wren’s at Oxford, attempted to inject a dog with warm milk and broth. These experiments… were less successful. But they made Lower ponder whether two canines could exchange blood. Can blood be transferred if it is nourishing?

Lower successfully transfused blood between two dogs in 1665. After the test researchers all over Europe started experimenting with transferring blood from one animal to another. However, these researchers questioned whether transfusion would affect the recipient. A list of queries about transfusion was written by Robert Boyle, who is well known for his work on gases. He pondered things like if a cowardly dog’s blood might make a strong dog more docile. Or whether a poodle transfusion would lead a dog with straight hair to have its fur curl. Additionally, researchers questioned if it was ever safe to transfuse blood into a human. A blood transfusion might endanger someone’s very soul if the connection between the blood and the soul exists.

A French physician named Jean-Baptiste Denys finally put an end to all of these concerns on June 15, 1667, by carrying out the first-ever successful human blood transfusion. Animal transfusions were something Jean-Baptiste Denys was already adept at. In order to demonstrate that circulation existed, he carried out open transfusions on the Seine River’s banks in Paris. In front of a live audience, Denys invited gentlemen, noblewomen, and commoners as he transfused blood between dogs. Denys rejected the idea of utilizing human blood, calling it barbaric to shorten one man’s life in order to prolong another’s. Instead, he made the decision to use animal blood, arguing that since animals didn’t drink or swear, it had fewer contaminants than human blood.

A 16-year-old with fevers received lamb’s blood from Denys in June 1667. The youngster was pronounced healed by the doctor. Then Denys administered lamb’s blood transfusion to a butcher. The butcher was in a good mood after the surgery, so he killed the lamb on the examination table and brought it home for dinner. Following Denys’ successful transfusion of human blood, other nations raced to carry out their own transfusions.

A Sheep-Man?

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisaradio/MZPYAD3HPFNXBCYZY4MFSHHMWM.jpg)

The English Royal Society scientists planned their own human-animal transfusion in November of 1667. They selected Arthur Coga, a mentally unstable man with a Cambridge education, as their subject. He only spoke Latin, and doctors noted that his brain was a touch too heated. The English researchers were hoping the transfusion of sheep blood would cure Coga of his mental condition and demonstrate that their transfusion process is superior to the French one.

A large group of people gathered under Richard Lower’s guidance to observe Coga’s transfusion. After Lower successfully infused Coga with lamb blood, Coga went back for a second transfusion a month later. Coga objected when the Royal Society researchers sought to schedule a third transfusion. He claimed that the transfusions had changed him into a literal sheep. Even going as far as signing his letters by the name “Coga The Sheep.” So the whole turning a man into a sheep thing, wasn’t a victory they hoped it would be.

But the murder of Antoine Mauroy in 1667 was actually the largest setback for the science of blood transfusions. Jean-Baptiste Denys attempted to treat Mauroy in Paris with calf blood, but after his third transfusion, Mauroy started suffering from seizures and passed away. After that, Denys was accused of killing Mauroy, and the trial was nothing short of chaos.

A neighbor claimed that Mauroy’s wife, Perrine, had murdered him and police had found mysterious and possibly deadly powders at her house. Another neighbor said that a mysterious doctor had paid him to testify that Mauroy had passed away during the blood transfusion. You should be aware that many doctors of the time were vehemently opposed to transfusions. Henri-Martin de la Martiniére, a former pirate doctor, was one of those opposed to the practice. He said that blood transfusions would promote the kidnapping of infants and cannibalism, which at the time seemed realistic. Martiniére still informed Denys in a letter, “allow me to tell you, Sir, that Satan reveals himself through your work.”

Martiniére even instructed Perrine Mauroy, whom he knew personally, to put the responsibility for her husband’s passing on Danys. In the end, Denys was cleared of all charges, but France outlawed blood transfusions as a dangerous practice.

The Efforts To Bring Back Washington

After a long and twisted journey through human-animal blood transfusions, human-sheep transformations, and murder trials, we eventually arrive on the evening of December 15, 1799, when William Thornton first saw George Washington’s frozen and lifeless body.

Thorton felt that by combining heat, air, and blood, he might still resurrect Washington even after rigermortis had taken hold. Thornton requested cold water so that it could gradually reheat the President’s body. Then, in order to provide warmth, he intended to cover the torso with blankets in a circular, overlapping pattern. Thornton was confident that by doing so, the process would warm the President’s frozen blood vessels. Thorton would conduct a tracheostomy after warming the patient’s body. Due to the lack of antibiotics and sterilization in the 18th century, this treatment was highly dangerous. But if it were done on a dead person, there would be less risk involved.

Thornton would artificially simulate breathing by filling George Washington’s lungs with air. The President’s life force would then be sparked using lamb’s blood, which would then supply the necessary energy. Thornton, who had no doubt read about Arthur Coga’s transfusion in the journal of the Royal Society, believe that if madness could be cured, so could reanimating a human.

In the end, the Washington family promptly overruled Thornton’s intention to bring the President back to life. They argued that it would be better to preserve the President’s legacy as “one who had departed full of honor and renown; free from the frailties of age, in full enjoyment of every faculty, and prepared for eternity” rather than deliberating with Thornton about whether it was possible to bring the President back. In other words, death was preferable to some sort of lamb’s blood-resurrected Frankenstein’s monster.

Thorton disagreed. Even two decades later, he wrote “there was no doubt in my mind that his restoration was possible.”